Despite seeing stronger revenues, African banks are facing a challenging path to recovery. Mohamed Dabo reports

In plotting their path to recovery, banks in each country will face their own set of challenges.

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

Future growth in revenues after risk costs are likely to differ significantly by country and will depend largely on volume growth and on the normalisation of provisioning levels.

The speed of recovery will vary depending on the scenario that unfolds, according to a study by global consulting firm McKinsey & Company.

Depending on which scenario prevails, growth in revenue after risk costs could vary between 9% and 21% compound annual growth rate over the next four years, off a low base in 2020.

The three scenarios

“Swift action and a focus on three imperatives could strengthen African banks and support recovery,” McKinsey & Co says.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe sudden and severe crisis brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic has dealt a cruel blow to African countries, threatening the lives and livelihoods of millions and causing a rapid economic contraction.

This has had knock-on effects for industries across the continent, including banking.

Now, as companies and leaders start to look toward recovery, new analysis from McKinsey provides some optimism.

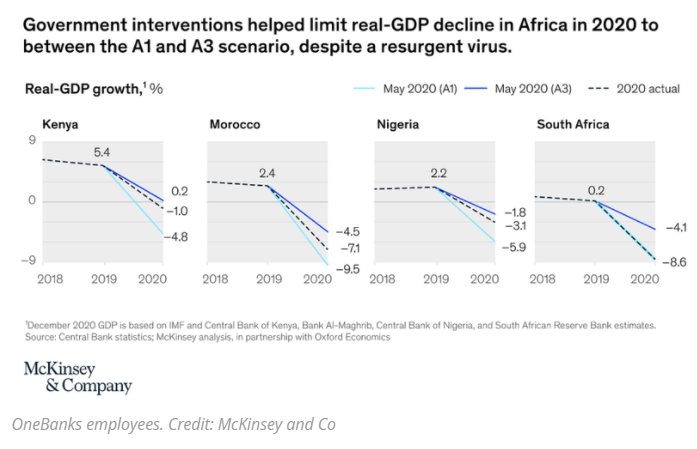

Government data and financials released by banks in four major economies on the continent (Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, and South Africa) show that, despite a resurgence of the virus, the pandemic’s impact on African banks in 2020 was less severe than initially expected.

And given the important role that banks play in the broader economy and society in Africa, this in turn could signal a faster recovery for the continent.

Unlike many past economic shocks, the Covid-19 crisis is not limited to banking; it is a humanitarian crisis and a crisis of the real economy, with banks being affected by cascading credit losses and uncertain demand.

In developed markets, McKinney & Co estimates that the average return on equity (ROE) for banks could dip below 1.5 percent in 2021 before recovering to precrisis levels of around 9 percent by 2024—this equates to five years of returns effectively lost for the banking sector.

The impact on African banks is likely to be less severe

“While the average ROE for African banks fell by 50 percent—to 7 percent in 2020, from 14 percent in 2019—we expect this to rebound to near precrisis levels within the next three years if economic recovery on the continent follows the scenario that a majority of global executives believe will most likely unfold,” McKinsey & Co says.

Drawing on McKinsey’s global research, as well as from real-world examples from across Africa’s banking sector, this article builds on the firm’s analysis in June 2020 to provide insights and analysis to help shape and accelerate this recovery.

“We believe that a focus on three imperatives—cantered around productivity, risk management, and scaling up technology—could help banks build core strength and resilience in the new reality,” it says.

A year into the Covid crisis, there’s now a better picture of the pandemic’s economic impact on the continent.

McKinsey has developed nine global macroeconomic scenarios, which reflect a range of virus-containment, public-health, and economic-policy responses.

The two scenarios most likely

The early consensus of global executives had been that the two scenarios most likely to prevail would be A1 (a recurrence of the virus and muted world recovery) and A3 (a contained virus and global growth returning in 2021).

It is now evident that the actual impact of the pandemic in 2020 for most major African economies was somewhere in between these two trajectories.

South Africa was an exception; existing weaknesses in that economy, coupled with a strict nationwide lockdown, led to a fall in GDP in line with our A1 scenario. This relative clarity has allowed us to refine our analysis and outlook for African banking in several key respects.

Real GDP across the four major markets we assessed declined by 6 percent in 2020—roughly halfway between estimates of 8 percent (A1) and 3 percent (A3).

While the virus was resurgent, its impact on banking revenues after risk costs was less severe than expected.

Post-risk revenues declined by 18 percent in 2020, compared with 21 percent estimated in the A1 scenario on the back of a combination of factors, including government fiscal interventions and the easing of lockdowns.

In Kenya and Morocco, for example, the relaxation of lockdowns and curfews in mid-2020 slowed the expected economic decline, despite challenges in the agricultural sector, including locust swarms in Kenya and drought in Morocco.

In Nigeria, the partial recovery of oil prices and the lifting of restrictions also led to a gentler decline in GDP of –3.1 percent, between the A1 and A3 estimates of –5.9 and –1.8 percent, respectively.

Government support programmes—including moratoriums on repayments and credit infusions such as loan-guarantee schemes—combined with low interest rates and a decline in nondiscretionary spending played a key role here, helping to increase affordability and to support loan and deposit volume growth.

The sharp fall in interest rates together with lower transaction volumes and fee waivers led to a decline in client-driven interest and fee revenues.

Overall, lower economic activity and higher unemployment have increased banks’ risk on loans, leading to higher loan-loss provisioning.