All eyes are on the November US presidential election, and with the polls predicting a change of administration, just what will that mean for US banks? But as Ivan Castano reports, no matter who wins the election, Covid means more pain ahead for the sector

The coronavirus has thrown the US banking industry into a state of extensive chaos. Loan defaults, particularly in the commercial real estate sector, are fuelling losses while rock-bottom interest rates are squeezing margins. Firms are set to provision billions against a worsening outlook, and there are mounting concerns about a new foreclosure crisis.

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

“Things are not looking good,” confirms Ruth Razook, founder and CEO at industry consultancy RLR Management. “We are probably going to see two or three more quarters of losses and more capital provisions,” depending on how fast a Covid-19 vaccine arrives to help the world’s largest economy – which plunged 32% during the lockdown months – emerge from recession.

Banks set aside $39bn to cover virus losses in the second quarter, up 280% from the prioryear period, according to market regulator FDIC. Delinquent loans, meanwhile, surged 15%, led by an 87% hike in commercial real estate and industrial loan losses.

Wells Fargo saw the biggest hit from the disease, which dealt it a double whammy as it was already suffering under a consumer fraud scandal. The bank reported a $2.4bn loss last quarter, down from a $6.5bn profit last time. Meanwhile, credit charges totalled $9.5bn, forcing it to slash its quarterly dividend – a U-turn compared to other large banks which managed to keep such payouts.

Defaults reach 25%

Amid deep losses in retail, travel, entertainment and energy, loan defaults could tip 25% by year-end, Razook predicts. She expects profits for the nation’s banks to decline around 70% this year, down from $233bn in 2019 when they slipped 1.5%, according to the FDIC.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataLayoffs are also set to balloon as banks shutter branches to accelerate a shift to digital. Wells Fargo, for instance, is expected to cut 50,000-66,000 or 20-25% of its workforce in the near to medium term as part of an aggressive cost-cutting effort.

As office towers and shopping malls sit near empty, commercial property managers are facing a grim outlook.

“The biggest worry is the commercial real estate portfolio, which is getting hit by losses in the hospitality, hotel and entertainment sector,” concedes Karen Neely, general counsel at the Independent Bankers Association of Texas.

“If they don’t have revenues, how are they going to pay their loans? Oil and gas is also a big issue, at least here in Texas, and agriculture has suffered a lot amid the Trump tariff wars.”

Depending on their size and geographical reach, some institutions will have to book write-offs beyond those recorded from April to June, which were already up 100% from the January-March period for some lenders, analysts say.

$265bn on bad debts

More specifically, Accenture expects US banks to provision $265bn against bad credits this year, up nearly five-fold from $55bn in 2019, it said in a recent report.

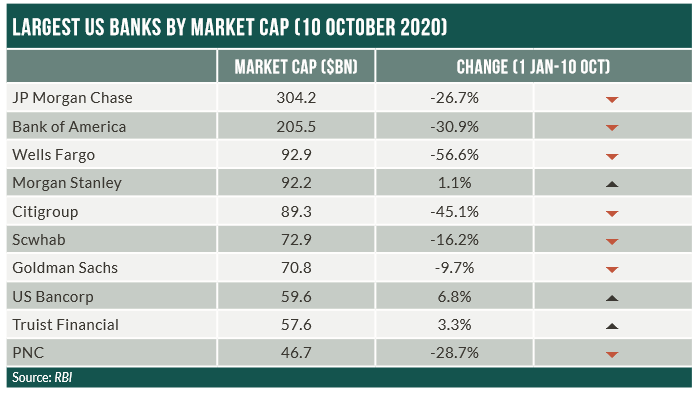

The bulk of the losses will stem from business-related property defaults, which rose 144% to $2.6bn in the second quarter, with JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America and Wells Fargo holding the largest portfolio of hotel, mall or industrial/warehouse assets. The affected assets now equal to 9%, 13% and 25% of their ‘tier-one’ essential capital ratios respectively, according to S&P.

As portfolios deteriorate, investors holding commercial mortgage-backed securities are increasingly nervous as their values decline, evoking memories of similar pandemonium during the 2007-09 meltdown caused by the subprime mortgage crisis.

Things may not be so bad this time around, however. The economy is showing encouraging signs of strengthening after unemployment declined sharply in August, leaving the jobless rate at 8.4%, down sharply from 15% at the height of the coronavirus in April. The latest reading put the unemployment rate below its 2007-09 peak, stoking hopes that the economy will begin to rebound in the second half of 2020.

Francisco Covas, research director at advocacy group Bank Policy Institute, says the worst appears to be over for banks. This is mainly because during the latest Fed stress test, lenders showed they have ample liquidity to survive a protracted – and even double-dip – recession.

V-, U- and W-shaped tests

The exercise demonstrated that banks could sustain $530bn in losses and still pay dividends while executing share buybacks, according to Covas’s research.

Crucially, “unemployment would have to go to 17% from 8.3% now over the next two years for those losses to happen,” he notes.

The Fed was even more optimistic. It noted lenders have enough equity to withstand $560bn-700bn in losses as part of an additional “sensitivity analysis” assessing operating dynamics in V-shaped, U-shaped and W-shaped (or double-dip recession) scenarios.

The survey assumed unemployment peaking at 15.6-19.5%, and excluded the effect of government stimulus payments and unemployment insurance, which have backstopped the economy this year but which survival remains in limbo as lawmakers spar in Congress. As part of its strategy to shore up the sector, the central bank has asked firms to halt share buybacks and cap dividend payments until future reviews.

While conceding that 2020 will bring losses, Covas expects the financial sector to recover much quicker than originally predicted. “At 8.3%, unemployment is much better than many expected,” he says. “It’s true that travel and retail have been affected, but they are starting to pick up and the services sector is doing well.”

Some hedge fund managers and analysts, notably George Soros – the infamous billionaire who shorted the Bank of England – agree that the outlook is improving, and have signalled bank shares as the best recovery play once a vaccine is out, presumably this autumn.

Are bank stocks a buy?

They claim leading institutions such as Citi, JP Morgan and Bank of America have offset losses by bolstering investment banking revenues while many stocks trade at historically low valuations after declining more than 30% in the pandemic’s aftermath.

Not everyone agrees, however. “I don’t see this as a good time to buy,” says Deborah Fuhr, founder at exchange-traded fund consultancy ETFGI, who is advising clients avoid banks, also as interest rates are expected to hover around zero for a while, squeezing profits. “People are facing evictions and will have difficulties paying loans and mortgages. The backdrop is difficult for banks,” she says.

Regardless of who is right, the November presidential elections will surely have a decisive impact on the sector.

Trump Vs Biden

A Trump win would maintain the business status quo of low corporate taxes and deregulation. However, Neely says the industry can also thrive under a Biden win, echoing views that the president’s virus “mismanagement” could continue, further damaging the economic recovery.

Says Neely: “Biden has been crystal clear that he will attempt to restructure tax laws. But a healthier economic environment would offset any tax increases. Businesses would get back to normal because the right steps would be placed to reopen safely.”

Asked whether a vaccine’s imminent arrival would render the speed of the economic reopening irrelevant, Neely counters that phase III trials could take longer than expected, as the AstraZeneca delays recently showed. “We are going to get vaccines amazingly fast, but not as fast as Trump has promised.”

On a more positive note, the crisis has been a disguised blessing for companies working to become digitised, says the lawyer, noting that banks will be able cut operating costs by around 10% from closing – or opting not to reopen – thousands of branches as more people bank online and work from home.

“The cost side of banking is going to change due to more teleworking and effective technology use to push customers to bank online and deliver services in a different way,” she predicts.

Digital push

Strategic partnerships between traditional lenders and digital institutions operating mobile apps targeting bank-wary millennials or unbanked citizens are also set to spring up. And M&A deals, especially between small and mid-size banks, should also gather steam as firms look to boost economies of scale.

Before Covid-19 emerged in Wuhan around Christmas last year, digital banking accounted for just 7% of US banking. But in the past few months, its share has jumped to 12%, underscoring the rapid shift to internet banking.

“Before the crisis, banks were not rushing to go digital,” says Razook. “Now they are accelerating the trend, which I see tripling to 35% next year.”