COP28 host the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is among 28 petrostates that risk losing over half their revenues from fossil fuels by 2040 as the energy transition accelerates and climate policies tighten, according to new research from financial think tank Carbon Tracker.

“Electricity is expanding to become the basis of our entire energy system, driven by falling costs of wind, solar and batteries,” said Guy Prince, senior oil and gas analyst at Carbon Tracker and author of the report, in a press statement. “This is a profound threat to oil and gas exporting nations, because falling demand for oil and gas is likely to lead to a significant fall in future revenues. Governments should waste no time in reducing their dependence on fossil fuel revenues and take steps to make their economies more resilient and better equipped for a low-carbon future.”

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

Demand for oil and gas is expected to start declining before the end of the decade, with the subsequent oversupply likely to result in falling prices. This, the report warns, will leave a large hole in the public finances of the world’s petrostates, even those with the lowest cost of production, hampering their ability to fund public services and threatening their stability.

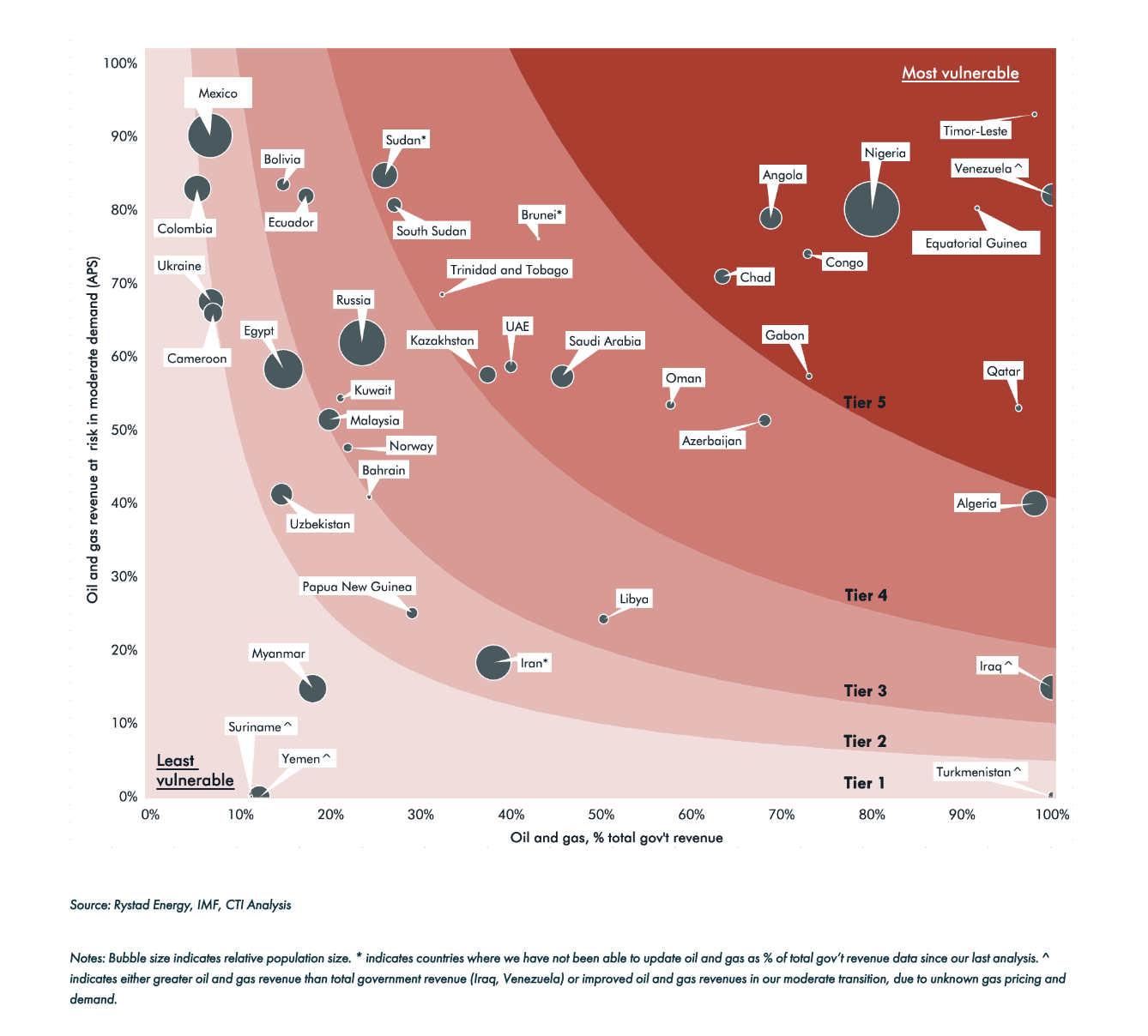

The ‘Petrostates of Decline’ report, released on 1 December, analyses the potential fossil-fuel revenues of 40 oil and gas dependent countries between 2023 and 2040 in the scenario of a moderately paced energy transition that limits global warming to 1.8°C. The nations’ revenues will fall from an expected $17trn to just $9trn, the research found.

“In many petrostates, a political settlement has become established where citizens expect high public sector salaries and low or zero-income taxes along with a generous welfare state,” said Prince. “Restructuring their economies is likely to require parallel political reforms to make lawmakers more accountable and give citizens greater representation.”

Governments are adopting increasingly tough climate policies as natural disasters proliferate and intensify, and the global carbon budget – the amount of carbon that can be safely emitted for the world to stay within a 50% chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C – looks likely to be blown before the decade’s end.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataAs COP28 kicked off in Dubai, nearly 120 countries backed a goal to triple renewables and double energy efficiency by 2030. Language calling for a “phasedown/out” of “fossil fuels” and “coal” – with negotiators still to decide on the final wording – was also included in a first draft text circulated at the COP. Some are pushing for a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The ever-decreasing cost of renewable energies and electric vehicles, along with the energy security concerns spotlighted by the Ukraine War, is diminishing demand for oil and gas. According to the IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2023, demand for oil will fall from 100 million barrels a day (b/d) in 2019 to 92.5 million b/d in 2030 and 54.5 million b/d in 2050 if current national policy pledges are fulfilled.

Carbon Tracker warns that a country like the UAE relies on oil and gas for 40% of government income, but faces a 60% drop in production revenue. Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter, is in a similar situation. In Africa, Nigeria, Angola, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon all rely on oil and gas for over 60% of their total budgets; and all but Gabon face a 70% reduction in expected oil and gas revenues. Venezuela is the country most at risk, with its public finances entirely dependent on oil and gas revenues, which could be over 80% lower than forecast.

Petrostate governments earn fossil fuel revenues either through state-owned national oil companies (NOCs) or through taxing oil and gas production. But when demand falls, declining prices reduce these revenues and can render some projects uneconomic. The highest cost producers will suffer the most, and a moderate transition is likely to make redundant over 50% of new projects belonging to NOCs Rosneft (Russia), Ecopetrol (Colombia; this became the tenth government to join the call for a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty on 2 December) and Pemex (Mexico).

Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

However, price slumps will impact all petrostates. Countries in the Middle East and North Africa will see 45% less oil and gas revenues under a moderate transition than a slow one, with nations in Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa suffering even more.

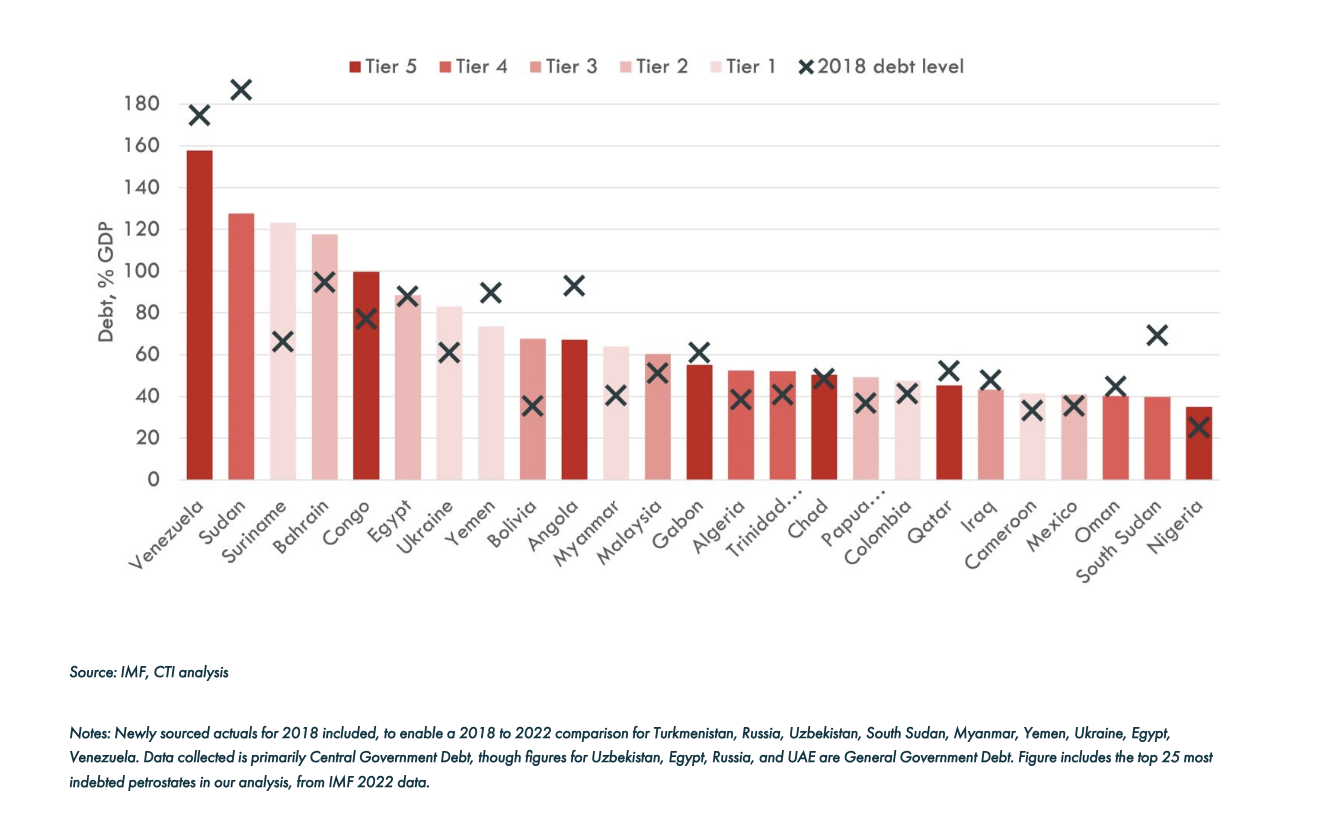

Petrostates also face other threats to their stability, including rising national debt levels, fast growing populations, uneven levels of development and fragile political institutions. Central bank debt in the 33 petrostates the IMF has consistent data on doubled on average from 24% in 2010 to 46% in 2018. And Africa’s population, for example, is set to double to 2.5bn by 2050. “Clearly, such rapidly growing populations in oil and gas revenue dependent states, that are relatively less developed, is a dangerous combination in a future of declining oil and gas demand,” said Prince.

The report calls on petrostates to diversify their economies and strategically build up new sectors, broaden their tax bases to bring in more income, end subsidies for fossil fuel consumption to reduce pressure on public finances, and invest in sovereign wealth funds while progressively reducing the proportion of fossil-fuel revenues in current spending.

Speaking to Energy Monitor, Prince points out there are “some positive examples of economic diversification”, for example, Dubai: oil once accounted for 50% of its GDP but today it represents just 1%, with the country having developed a dynamic economy based on import and export logistics, property, tourism and finance. In contrast, Dubai’s neighbouring emirate, Abu Dhabi, is still largely reliant on oil.

“Other countries yet to diversify could follow similar strategies depending on their location and emerging sectors,” says Prince, though he notes that “on the whole, when you look at the potential revenue shortfalls”, countries have not responded “with the sort urgency that you would expect”.

To deliver reforms, petrostates will likely need international financial and technical support, states the research. “The international community more broadly has a clear stake in supporting petrostates through this process, both for development reasons and to mitigate the very real risk of conflict and instability if these countries are hit hard by the energy transition,” said Prince.

Just Energy Transition Partnerships, despite their focus to date on coal phaseouts, offer a possible model for collaboration with lender or donor countries, suggests Carbon Tracker. Regional cooperation could also see petrostates create shared infrastructure with their neighbours and develop complementary trade strategies.

Editor’s note: Data journalist Polly Bindman contributed reporting from COP28 in Dubai.